Dear leader,

You’re always accountable for what your part of the organization does.

This is manifested by law for top management, and in most organizations, this expectation ripples down the leader hierarchy. You are held accountable by the leader above you, and you work to keep your employees accountable to the organization. You wish to know the person you can go to when things are not going according to plan.

Western culture deeply ingrains a focus on individual accountability. Even though we know that few business successes have been achieved by individuals, we tend to celebrate the individual at the top of the organization. When things go wrong, we tend to look for an individual who made a mistake further down the ladder.

We know that it is too simplistic. Any business challenge is a complex combination of market, customers, users, technologies, etc., that all continuously develops. Business success is the sum of many decisions made by accountable people throughout the organization daily.

Organizations worldwide have successfully implemented autonomous cross-functional teams to achieve the needed business agility. Using the diverse skill sets in the team, they cope with the complexity of the multiple dimensions and iterate toward optimal solutions for the customers.

This, however, definitively breaks the illusion of a simple chain of single accountability. At the organization’s lowest level, every decision results from collaboration between a diverse group of people, who collectively balance the many concerns that each represents.

Many leaders experience a glass floor between them and these autonomous teams. They find it hard to enforce accountability like they did before. I previously wrote a little piece1 about this frustration and gave some examples of how team members are not only focussing on their individual success but also can contribute to the greater good of the organization.

In this article, I aim to illustrate how you as a leader can organize and work with autonomous cross-functional teams and secure accountability not only to local success but also to the organization as a whole. Cross-organizational accountability is necessary if you want customers/users to have a cohesive experience and if you want higher productivity through, e.g., standardization and reuse.

First, however, a short introduction to how accountability is understood and how to nurture that.

Accountability and motivation

Many researchers2 have tried to uncover accountability and how to achieve that. Accountability means the willingness to achieve the goals you’ve set or have been set for you within given boundaries, owning the actions you take and the outcomes you create. Accountability means doing your utmost to deliver while living up to legal boundaries, time, quality, financial constraints, etc., and being transparent around the compromises you’ll have to make when the boundaries are too tight.

Besides clarity about goals and boundaries, the major component of accountability is individual motivation. These main drivers for accountability are something that you influence a lot as a leader of other people. However, how you do this differs greatly depending on whether we’re talking about individuals, teams, or a whole organization.

Let’s explore that a bit.

When you want an individual to solve a task on their own, you’ll typically describe the desired result rather concretely, and you may expect that the individual will bring motivation themselves. You may have read Daniel Pink3 or Self-Determination Theory (SDT)4 and know autonomy, mastery, purpose, and connectedness with others are vital for intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation is the primary source of motivation for complex tasks. Actually, external motivation can work counterproductive5.

Therefore, as their leader, you can increase the chance that they deliver accountably, i.e., timely, qualitative, and valuable work. For example, you can communicate the purpose of the work (purpose), allow them to deliver quality autonomously, i.e., based on what they believe is the best way (mastery), and ensure that they are part of a well-functioning community (connectedness).

Much has been written about motivation in the references mentioned, so let’s skip that here. It’s enough to point out that neither motivation nor autonomy are goals in themselves; that is, accountability, i.e., productivity, engagement, and persistence.

In summary, you as a leader should align with the individual around expectations and the boundaries within which these expectations should be met. I deliberately use the term boundaries because they would be the compromises you expect them to make, for example, because of a time limit. According to Daniel Pink/SD-theory, these reductions of autonomy reduce motivation and the good qualities that come from that.

Let’s move on and investigate what happens when accountability is related to a team or a whole organization.

Accountability in teams

If we scale up to teams, our expectations as leaders of what a cross-functional team can do collectively using all their different skills will change. The tasks they can solve are much more complex because they collectively know the market and their users, how to make great user interfaces (UI), how to make the solutions stable and scalable to thousands of concurrent users, etc.

No leader can match that insight and knowledge in each area of expertise—maybe one or two, but never all. Therefore, delegating more decisions to the team makes good sense—but which and how? For team members with different areas of expertise to make the right decisions, they must align around what they should create.

Intuitively, it follows from the theories mentioned above, the alignment of team member perspectives reduces individual autonomy.

You may have read/watched how Henrik Kniberg has explained how Spotify sees that differently6.

Instead of seeing alignment and autonomy as opposite, they believed that alignment enables autonomy. If everybody in a team can do whatever they desire, the resulting force could be zero, compared to the team members aligning around the same goal.

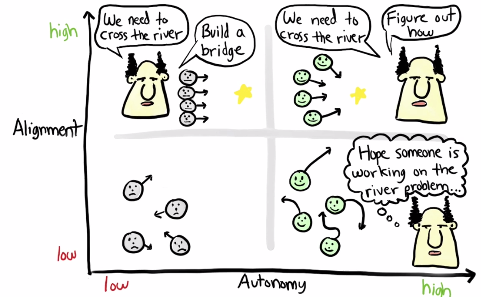

In essence, the Spotify leader, instead of telling each team member what to do (“build a bridge”) or hoping that they will figure out themselves what to do (“hope someone…”), the leader tells what they should achieve (“we need to cross the river” in figure 1). This leaves it up to the team to align on how they best, together, can accomplish that goal.

With all respect to Kniberg, I think that based on the previous section, we must conclude that this explanation is too simplistic. Using the terminology above, it is my interpretation and experience that the leader substitutes a more specific goal with a goal closer to the purpose, i.e., the value to the world rather than a specific item.

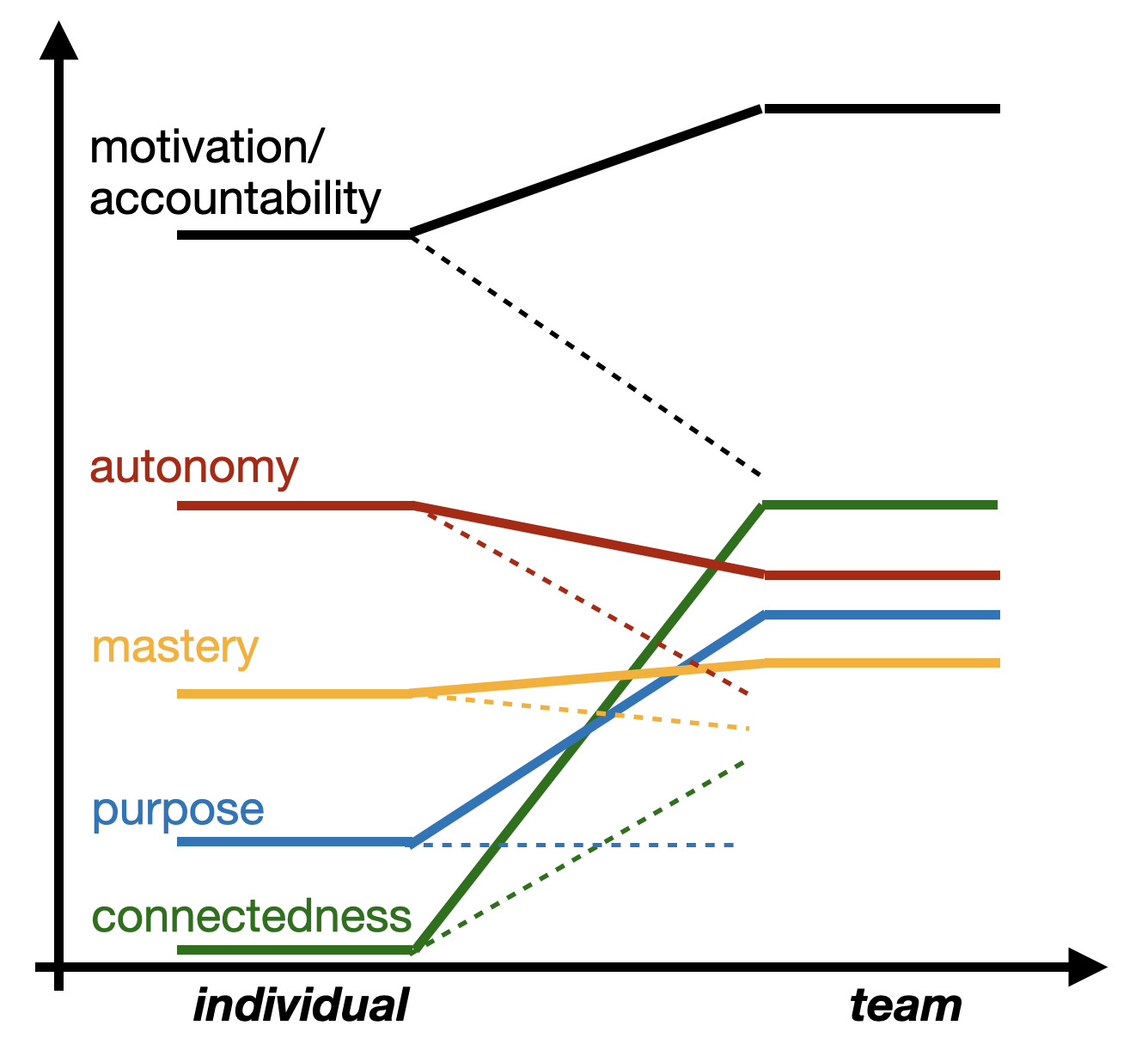

In the figure to the right, I have tried to illustrate what actually happens: The individual team members surrender some of their autonomy to the team. They optimize their contribution to reaching the common goal at the price of limiting their own solution space and deeper preferences, i.e., their autonomy (the full red line).

Instead, they get more purpose (“crossing the river” has more meaning than “you chop some wood for a bridge”), and they get connectedness in the team (full blue and green lines, respectively). The team provides a place of belonging, a place of mutual trust, and options of collectively learning (the full yellow line). That is if it is done well.

If not done well, it is not only autonomy that drops; all parameters that contribute to motivation can drop, and hence the accountability (illustrated with dotted lines). That means we lose what we’ve set out for in terms of productivity, engagement, etc.

So, leaders who do well at Spotify (and everywhere else) gain alignment, more motivation, and, hence, more accountability.

However, it is more challenging than it may sound, and therefore, autonomous teams have members who take leadership roles and ensure this team’s internal alignment happens. These roles are often called Product Owners (PO) and Scrum masters/Agile coaches.

This works very well as long as the teams in an organization are autonomous, i.e., independent of other teams. In Spotify, that was still possible in 2014, when the video is from, because they invested heavily in making teams as autonomous as possible through Continuous Delivery, decoupling modules, services, etc. At that time, they were a few hundred developers, but since they’ve become thousands and no longer work as described in the videos.

Unfortunately, they haven’t detailed their working methods in such detail since. Therefore, the principles shared in the remainder of this article are based on my experiences securing accountability in more extensive and mature organizations.

Accountability and the whole organization

What happens to accountability when you must ensure accountability beyond a few autonomous cross-functional teams? When your organization and/or products become so large and complex that teams cannot work independently but must share users, technology, infrastructure, etc.?

What if you want to lead your organization in the spirit of highly motivated, accountable teams? Building on what we learned above, individuals need autonomy, mastery, purpose, and connectedness to deliver at the highest level. Before continuing, I’ll emphasize that I am a big proponent of autonomous teams and that the first choice should always be to limit dependencies before anything else.

I’ll start by splitting accountability that leaders typically have into two parts:

- accountability toward the business, i.e., the product we sell to our customers/users, and

- accountability toward how we work together to achieve the former: proficiency accountability.

I have chosen the word proficiency since it stresses ongoing development, excellence, and responsibility for maintaining skillfulness across the board.

The two forms are different in some fundamental dimensions, and therefore I believe it makes good sense to handle them separately from a leadership perspective:

| Business accountability | Proficiency accountability |

| Target to make users able to solve their tasks better | Target to make developers able to solve their tasks better i.e. create better solutions |

| Goal is to increase value proposition for customers | Goal is to build effectively |

| Profit through value creation | Profit through efficiency |

I believe providing business results and creating proficiency are fundamentally two different leadership challenges, especially because cross-functional teams require proficiency in many technologies.

As mentioned, the leadership in cross-functional autonomous teams is already split between two roles: PO (business) and Agile Coach (team proficiency) and in the following, where I will discuss accountability at organizational scale, I will handle the two perspectices separately, as different roles. It is in great contrast to traditional management where the manager has responsiblility for all aspects of their employees: what they do (business), how they do it (proficiency) and personal elements. I am sure it makes sense to dive into the two dimensions separately and then discuss at the end if it makes sense that one manager can hold both roles.

Business Accountability

As a leader it is important to ensure our employees business accountability, i.e. that they work in the desired direction of the business.

Business accountability in a single team was achieved in Spotify by asking a stable team to solve problems (“cross the river”) for the users rather than just asking for some functionality (“build a bridge”) thus increasing purpose and connectedness for team members.

When you have several teams working on the same product, they need to be aligned to move in the same direction so the combined force of their efforts points in the most valuable direction for customers/users. Depending on the number of teams and their level of autonomy, it can be possible for them to align themselves typically in frequent collaboration between POs. However, there is a limit to how many POs can collaborate this way and, at the same time, secure alignment within their own team. At some point, the complexity of the business and the amount of parallel work will be so significant that it is beneficial to add another leadership role that can dedicate itself to the alignment of many teams around the business. They are typically called the Product Managers (PM).

The PM’s responsibility is to secure alignment in teams around the business strategy at a higher level. That alignment reduces the teams’ autonomy because they no longer decide the direction of the product they’re working on. Decisions by the PM and the other teams limit each team’s degrees of freedom.

How can a PM avoid reducing autonomy too much, and hence influencing motivation and accountability?

An approach that I’ve seen work is that the PM focuses on the product strategy, for example articulated in a vision, a business model, a blue strategy canvas, a value stream map, goals, etc., so everybody involved has a chance to understand the purpose and outcome of the collective effort of all teams collaborating. That substitutes the surrendered autonomy with more purpose.

The great PM involves PO/teams heavily in this strategy work, and (s)he refrains from coming up with solutions themselves – to maintain much autonomy. The PM instead uses the method of briefing and back briefing7 to make sure that the alignment goes all the way to the teamlevel decisions. To save you the effort of reading Bungay’s book, the briefing could be the strategic artifacts I listed above, and the back briefing from POs/teams could be a map/list of the user outcomes that they believe would meet the part of the strategy they are supposed to work on.

I have written about this way of strategizing at more levels in more detail in an article8 based on my articles about Agile Planning Circles9,10,. In relation to this article about achieving accountability through alignment, you should note that business alignment can be achieved by:

- Give your strategic brief, preferably using visual artifacts as those previously mentioned

- Involve the PO/teams in developing those artifacts and dividing the work amongst themselves

- Validate their back brief against your brief, and if you’re not satisfied, start working on your own brief to clarify your intentions.

- Remember that the people who create the real product work in teams. They understand the complex details and can quickly validate hypotheses with tight feedback from users.

- Doing this correctly will preserve motivation, accountability, etc in the teams.

So far, I’ve discussed the alignment needed to deliver the product that best meets customers’ and users’ needs with accountability.

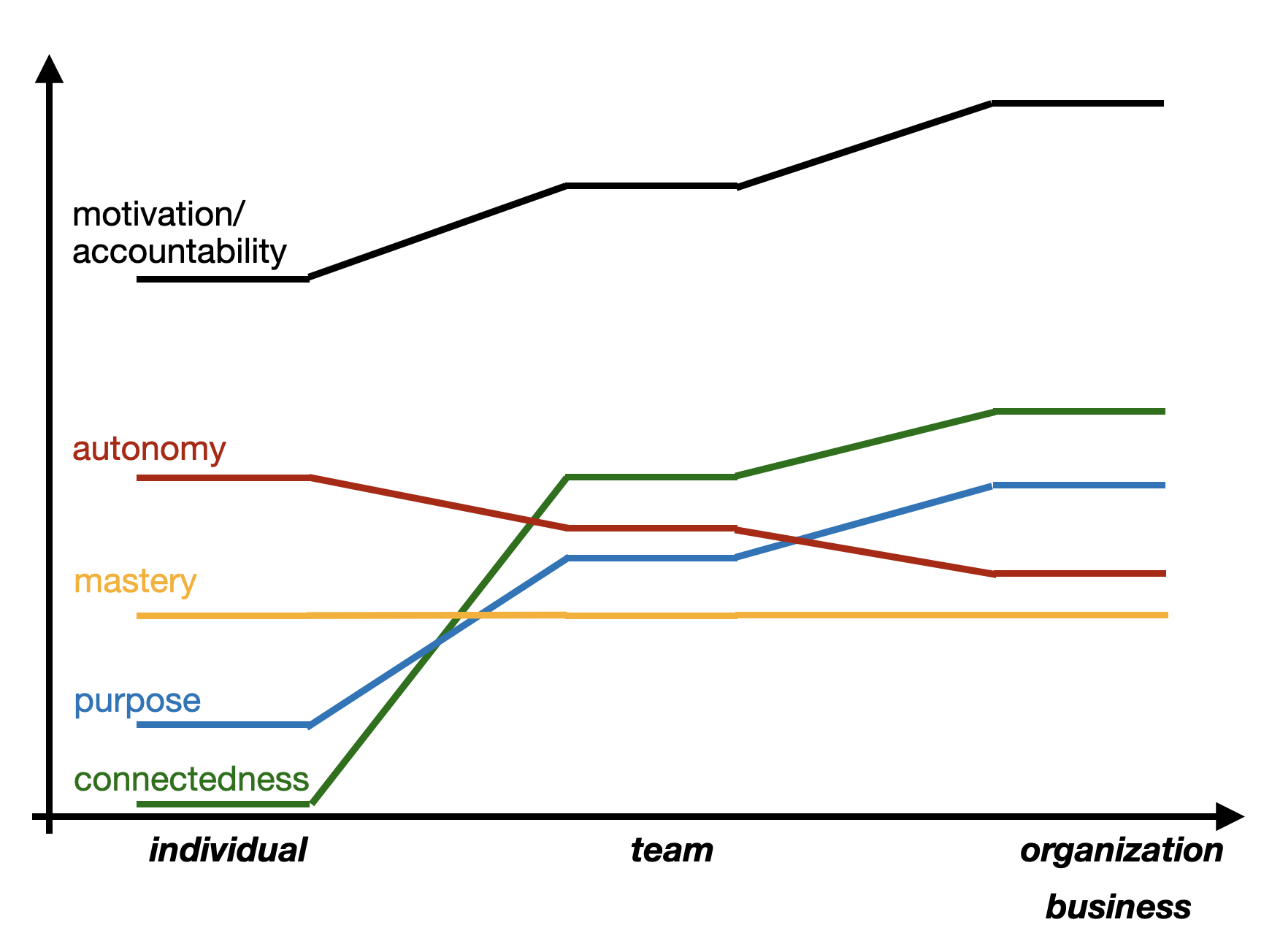

The individual surrenders some of their autonomy to be part of a team and succeed together in creating outcomes for users, and those teams again surrender some of their autonomy when they, together with other teams as a whole organization (connectedness), solve very complex problems for customers (purpose), as illustrated above. I.e. you create the business accountability expected from teams and individuals through increased purpose and connectedness.

As mentioned, creating the best solutions for customers and users also requires collaboration across the organization in another dimension.

Proficiency accountability

When scaling above a single team, when several teams collaborate to deliver an outcome, we all intuitively understand that doing things the same way across teams must create synergies and constraints.

The intention of this alignment is obvious: By choosing tools, creating standards, building shared components, establishing shared infrastructure, buying standard systems, implementing security, securing compliance the same way, etc. …. the organization achieves in several ways:

- the solutions appear cohesive to the users

- reuse of components and systems supports higher productivity

- shared tools and platforms offload concerns from teams and individuals

These are all worthwhile benefits. Therefore, many organizations create support functions that are detached from the teams to ensure this. They reserve their specialists to set up guard rails for team members. However, organizational alignment reduces individuals’ and teams’ autonomy with nothing in return e.g. mastery, purpose, connectedness, and hence, motivation and accountability. Professionals like to pick their own solutions, materials, tools, etc.

Furthermore, in my experience, these support functions tend to optimize according to their preferences, which means that the needs of the teams queue up, with the consequence that teams either cannot achieve what they want. You lose accountability or they break the organizational alignment by going things their own way.

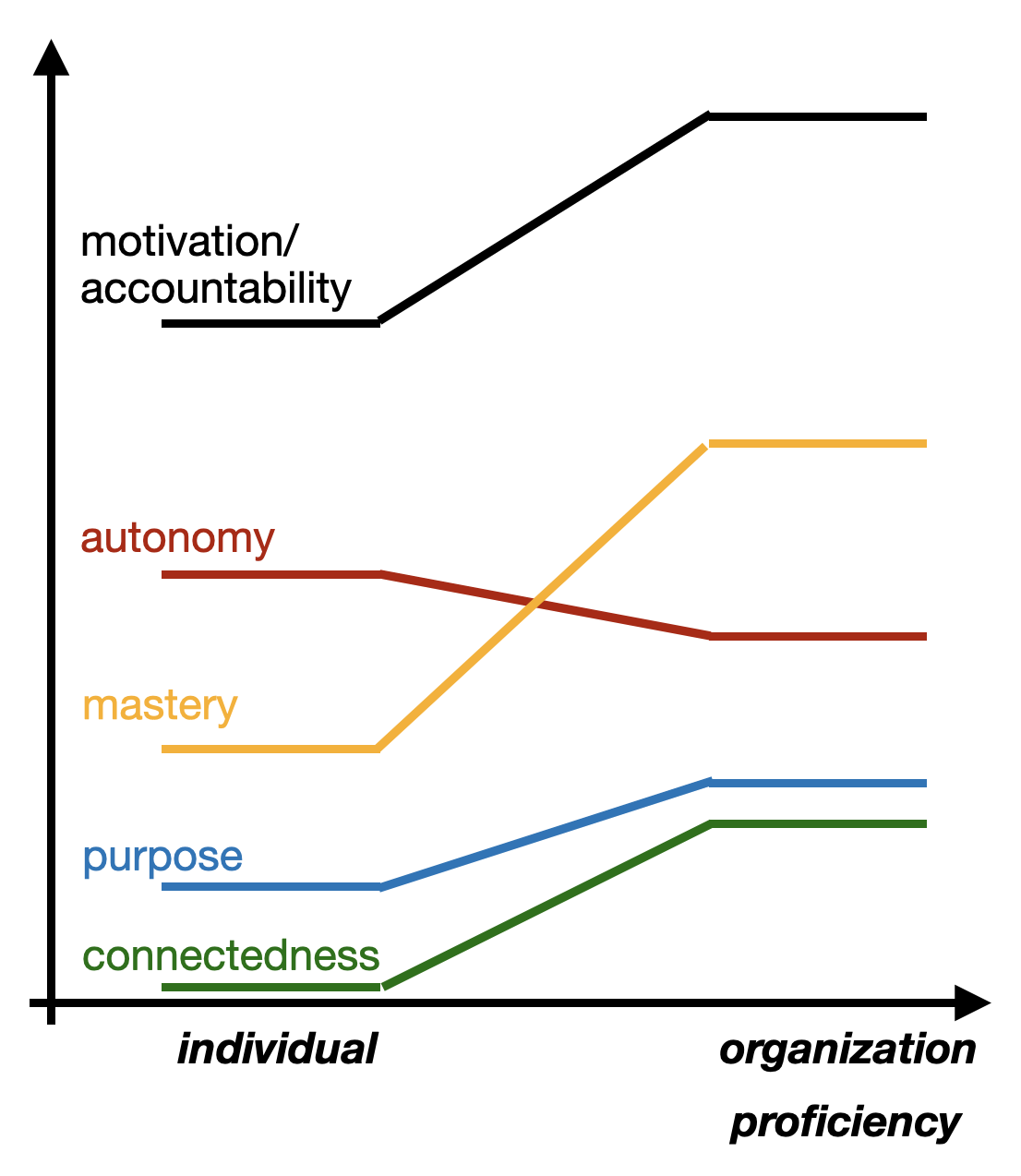

If you want proficiency accountability, you must preserve autonomy, mastery, purpose and connectedness. That can be done by involving the specialized team members in the proficiency decisions that affect them. You can delegate this organizational alignment to Communities of Practice (CoP), which are collaboration forums for individuals sharing skills or responsibilities across teams11. In Spotify lingo, CoPs are called Chapters and Guilds.

A CoP would then be responsible for tools, standards, etc., to be used by its members in their team roles. In terms of accountability and motivation, every individual is a member of the CoP, which matters most for their professional mastery. So, they are themselves part of the decision-making process that affects their autonomy regarding developing things like they prefer themselves—a lesser surrender of autonomy than to, e.g., support functions.

In return, the CoP-members get a place (connectedness) to discuss and learn with like-minded (mastery) and the purpose of lifting the whole organization to a higher level of proficiency (see illustration to the right). Well done, that secures accountability and powerful alignment.

I gave an example of this in my previous article1.

Leading a CoP

Since team members typically are 90-100% allocated to their team, CoPs do not have their capacity to establish standards, reusable components, technology infrastructure, etc. Therefore, members will take CoP tasks back to the teams, and the PO/PM needs to prioritize them for the common good of the whole organization over their immediate business outcomes. They need to trust that their team member has made the best decision and remind themselves that every time their teams invest extra time in building for the common good, all other teams do the same, and over time (s)he will gain cohesiveness, quality and longterm productivity.

In many organizations, it can be hard to empower CoPs with decision power and capacity without appointing a leader. In my experience, appointing a leader is almost essential

- to ensure accountability towards the rest of the organization,

- to facilitate the alignment between the individual members, and

- to evangelize the direction that the organization is moving within the CoPs area and

- reminding PMs/POs to invest their part in collective benefits

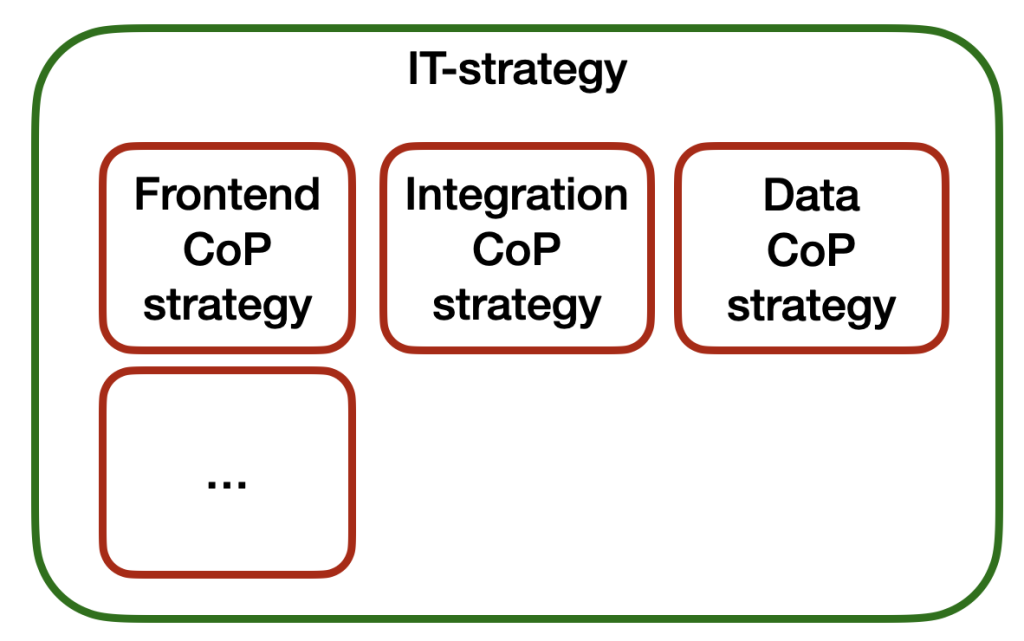

In that way, the leader of the CoP is similar to a Product Manager in terms of proficiency in their area, i.e., maintaining a clear strategy, executing through CoP members, and aligning with other CoP leaders as a complete strategy, e.g., an IT strategy (see illustration to the right).

They should preferably work as explained for the PM above ie. a lot of facilitated involvement and delegated responsibility for details, to secure the accountability of the members. Compared to the PM, they have the disadvantage of being unable to be together with the members every day.

Some organizations also appoint proficient CoP leaders as the personal leader for team members for several reasons:

- legislation requires that employees have a formal leader

- knowledge workers prefer leaders who understand their profession well

- to work strategically with, e.g., a technology area requires relatively deep insight

- It is hard to build a community with people who do not share expertise and you do not decide what they do (PO/PM) or how (CoP)

- remaining people work are exceptions since everyday issues are handled in the teams together with the SM

I am aware that this is a tighter definition of a CoP than, for example, Etienne Wenger’s. I do that because I want to emphasize what it takes to hold CoPs and members accountable for organizational alignment. Securing alignment and accountability when working with a CoP, for example, half a day a week, is challenging.

I realize that more detailed examples may be helpful, but since we’re already on page 8, I think it’ll serve you better if I reserve a whole article for that. Scaling CoPs and balancing them towards other ways of ensuring organizational alignment is also worth a deeper dive.

Accountability at organizational scale is based on alignment

Many organizations organize in cross-functional autonomous teams because they can better navigate in today’s complex business environments. Members of these development teams appreciate their professional autonomy, which conflicts with the traditional image of the all-knowing leader who is accountable and makes all decisions quickly.

No leader can have and maintain sufficient knowledge about business and every technology/skill involved in building solutions. Neither do they have time to be involved in every detail, becoming a decision bottleneck. If they try, they will lose the accountability of teams and employees, as illustrated in this article.

A solution to this is to make teams as autonomous as possible and let them make their own decisions within well-defined boundaries. When business and proficiency alignment is beneficial or needed due to the scale of the business, people should be involved.

This calls for a different kind of organization and leadership. Leaders should be skilled in either business—POs on the teams and PMs at scale—or proficiency—team members and CoP leaders at scale. I believe it is time for you to choose the direction you want: business or proficiency.

Leaders should own and maintain the strategy in their area and be able to brief their stakeholders and teams, who should transparently brief back on how they are accountable for working within these boundaries. The leaders should collaborate with piers to make their partial strategies into a whole for the organization, for example, a business or an IT strategy.

Done the right way, I claim that you as a leader not only can create the necessary alignment across the organization and do it better than time allowed before but at the same time increase accountability through

- empowered cross-functional teams (autonomy)

- clear, aligned strategies (purpose)

- skillful leadership with a growth mindset (mastery) and

- collective alignment around both business and proficiency (connectedness)

in teams and among employees. From their accountability comes your success.

It is time to let go of the illusion that the fastest way to make good decisions quickly is to brief a manager to make it. Quick decisions are made on the spot by team members who are well-aligned with good strategies – and those are the responsibility of leaders.

As a leader who wants to find the optimal balance between accountability and alignment in a large complex organization, I will recommend that you:

- train to think and brief your strategy using visual artifacts rather than having opinions on what should be done. Leave that to your team/CoP members

- train your facilitation skills

- trust your members’ decisions and leave space for continuously building their skills

- let go of your biases and listen

- invest in your relations across the organization

For all leaders (and any human being, for that matter), it’s a tall order to develop skills, behavior, and beliefs simultaneously, as the bullets above require. Still, it is necessary to live up to the accountability your superior expects from you. You can only be accountable if your employees are, and throughout this article, it has been the point that alignment is your power tool that replaces the belief that leaders are the best at everything. Leave the detailed decisions to those close to the actual work.

You cannot do it alone; you must use the knowledge and accountability of the whole organization – alignment replaces decision power.

—- THE END —-

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2025/03/05/your-glass-floor-is-their-glass-ceiling/

- Brené Brown, Stephen R. Covey, Christopher Avery, Simon Sinek, Karl Duncker, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi etc.

- Daniel Pink : Drive

- Edward Deci and Richard Ryan: https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/books/

- Popular summary of Daniel Pinks Drive: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1SfmmuC9IWs

- Henrik Kniberg : Spotify Engineering Culture Part 1 on YouTube

- Stephen Bungay : The Art Of Action

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2020/05/12/strategizing-over-strategy/

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2019/05/23/agile-planning-circles/

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2019/05/24/agile-planning-circles-the-artifacts/

- Etienne Wenger: https://www.amazon.com/Communities-Practice-Cognitive-Computational-Perspectives/dp/0521663636/